The Apple II got there first. It was the Wright Flyer I of personal computers.

When the Wright brothers made their historic first flight in 1903, lots of other inventors were trying to fling their own shoddy little planes into the air. And in 1977, when Steve Wozniak and Steve Jobs unveiled the Apple II, there were a zillion other nerds working on building a personal computer.

But Woz beat them to it, and Jobs knew how to sell it.

The Apple II was the product that turned Apple into Apple. It was the iPhone of its era, the product that redefined every machine like it that came afterward.

Its real magic was Wozniak’s minimalism. He integrated many technologies and components that no one else had put together in the same device, and he did it with as few parts as possible. It was, as Wozniak wrote in his autobiography, “the first low-cost computer which, out of the box, you didn’t have to be a geek to use.”

But as genius as Wozniak was, the Apple II almost didn’t make it out of his brain and into a product that the rest of the world could use.

Daniel Kottke, one of Apple’s first dozen employees, said, “[In 1976] the Apple II did not even work. Woz’s prototype worked. But when they laid it out as a circuit board, it did not work reliably… It was unacceptable. And Woz did not have the skills to fix that… But, it was even worse than that. They did not even have a schematic.”

Newly funded by investors, Apple had just hired Rod Holt as the company’s first engineering chief, and this was one of the big problems that Holt walked into when he took the job. At the time Woz’s Apple II prototype was a bunch of wires and chips in a cardboard shoebox. The tiny Apple team had to take this amazing concept machine and turn it into a product that could be manufactured and sold in stores.

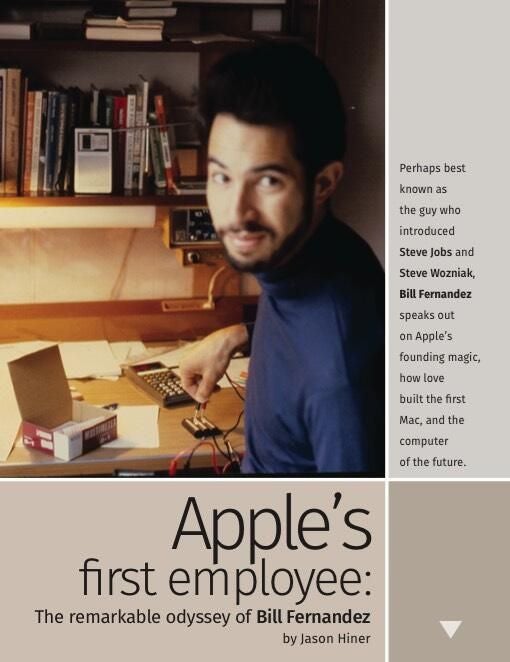

So Holt handed the first task to Apple technician Bill Fernandez.

When it came to computers and electronics, few people knew the workings of Wozniak’s mind better than Fernandez. The two had grown up as neighbors and had known each other since the fourth grade. In high school, Fernandez told Wozniak that there was a kid he needed to meet because he was into electronics and practical jokes just like Woz. It was a kid named Steve Jobs. Later, Wozniak acquired a bunch of different electronics parts and took them to Fernandez’s garage, where the pair worked on assembling the stuff into their own working computer that was years ahead of its time. Then, before Apple got started, Woz helped Fernandez get a technician job at Hewlett-Packard, where Wozniak was an entry-level engineer. So the two had a lot of history together.

In order to make the Apple II a buildable product, Apple needed a full technical readout of all the component parts, so that’s what Holt assigned to Fernandez.

“When Woz designed something, most of the design was in his head,” said Fernandez. “The only documentation he needed was a few pages of notes and sketches to remind him of the overall architecture and any tricky parts. What the company needed was a complete schematic showing all the components and exactly how they were wired together.”

That meant that Holt and Fernandez had to take the prototype that Wozniak had made and reverse engineer it to create something more standard and repeatable.

“Bill and Rod buzzed out the board to create the schematic from the logic board because they didn’t trust the schematics that they had,” said Kottke. “They did have the board, so they reverse engineered the board to create a schematic.”

Fernandez said, “I drew the first complete schematic of the Apple II, working from a few xeroxed pages of Woz’s notes written on graph paper. Having worked with Woz before… this was a straightforward [but] painstaking task. In my opinion, it was a beautiful schematic: logical, clear, easy to determine the relationships between components, and easy to follow the data and logic flows.”

It worked. The machine got built. History was made. Wozniak and Jobs became famous as the two crazy kids who started the computer revolution in a garage in California.

But our collective memories only have room for so many names, and history doesn’t usually remember little guys like Bill Fernandez, despite the fact that if it wasn’t for Fernandez, then the Apple II may have never become the machine that started the personal computer movement. In fact, if it wasn’t for Fernandez, there may have never even been a company named Apple Computer.

Cream soda pals

Silicon Valley created Bill Fernandez.

His parents met at Stanford University. They moved to Sunnyvale when he was five, and he spent his entire childhood growing up in that community, in a house that his mother decorated in a minimalist Japanese style that reflected her background in Far East Studies at Stanford.

The Fernandez family’s Eichler house was situated in a middle class neighborhood filled with engineers employed by the growing technology boom in Northern California. They worked at places like Hewlett-Packard, NASA Ames Research Center, Lockheed, and a number of technology contractors for the US defense industry. Many of them had personal workshops in their garages and were so passionate about the emerging tech boom that they loved to chat about it with eager neighborhood kids — and occasionally share parts and tools along with wisdom about circuits and wiring.

Fernandez said, “I love working in wood and sometimes wish that I’d grown up on a street of cabinet makers. But, I grew up on a street of electronic engineers.”

Bill’s father was a trial lawyer, superior court judge, and the mayor of Sunnyvale for a time. He described his mother as “a 1950s era super mom.”

By the time he was in middle school, Bill was hooked on electronics. When he was 13, he built a box with multicolored lights that could easily be turned on and off with a series of switches. When he was 14, he designed an electric lock that would engage or disengage based on a sequence of buttons. When he was 15, he made a TV jammer that could interrupt reception on a TV — Woz took it to college and harassed his classmates with it, and it was immortalized by a funny scene in the movie “Pirates of Silicon Valley.”

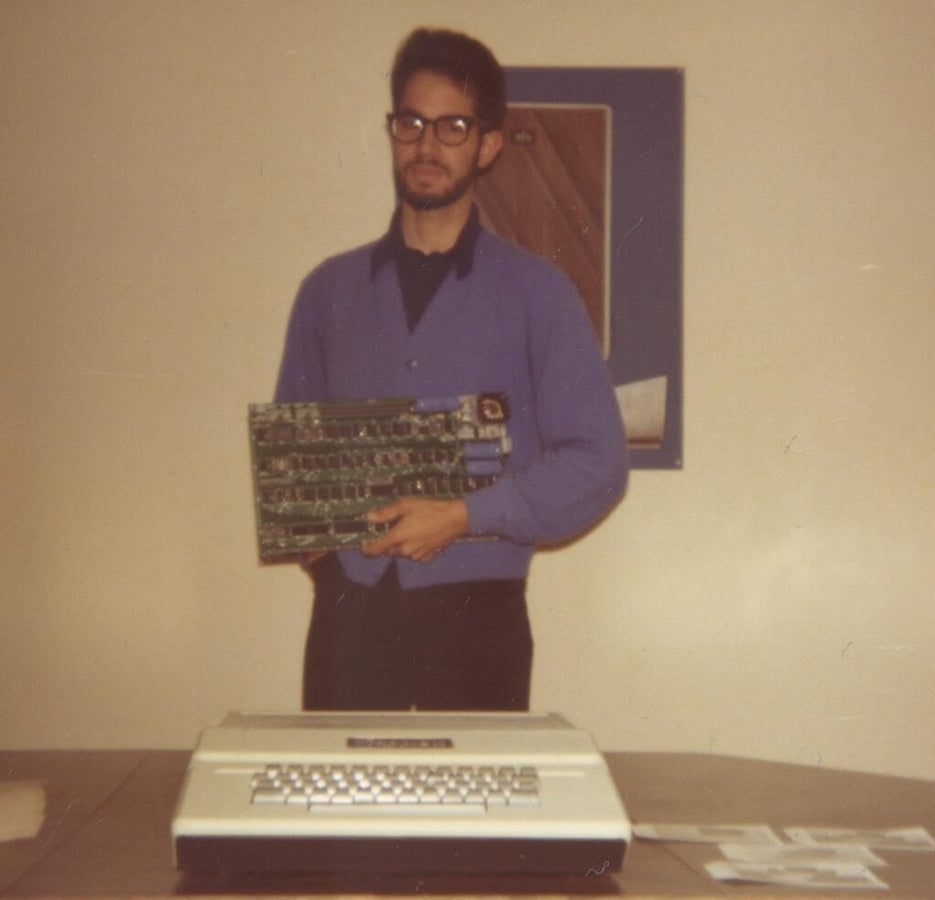

But in 1970 when Bill was 16 and Woz — who is four years older — was back from college, the two of them embarked on their most ambitious project yet. They decided to build their own computer from a collection of about 20 electronics parts that Woz had begged from Tenet, the technology company he was working for as a programmer. For years, Woz had been sketching out ideas for computers on paper, but he never had the hardware to try out his ideas about building a working computer with the fewest number of parts possible.

Once Woz acquired the parts, he took them to Fernandez’s garage, and the two of them set out to bring Woz’s paper sketches to life. By today’s standards, it looks like a rudimentary experiment, only a step above a glorified calculator. It had no microprocessor, screen, or keyboard. The machine merely processed punch cards and returned the input with a series of flashing lights. But, as a personal computer, it was several years ahead of its time, and it held the potential of doing a lot more.

They called it “The Cream Soda Computer” because while they were working on it in Fernandez’s garage they would take breaks and ride their bikes to the Safeway and get their favorite drink, Cragmont Cream Soda, and then drink it while they were building the machine.

A couple years earlier, Fernandez was walking through the neighborhood one day with Jobs when he spotted Woz washing his car and finally found the opportunity to introduce the two. They hit it off immediately.

“We were just kids, and they were just two electronics buddies,” said Fernandez.

Jobs and Fernandez had been friends since middle school, when Jobs moved into the same school district in Cupertino.

“We were both nerdy, socially inept, intellectual,” said Fernandez, “and we gravitated towards each other. We both also were not at all interested in the superficial bases upon which the other kids were basing their relationships, and we had no particular interest in living shallow lives to be accepted. So we didn’t have many friends.”

In middle school and high school, the two spent a lot of time together, particularly at the Fernandez house, where Jobs was attracted to the meticulous Japanese style that Fernandez’s mother used to decorate the place. In retrospect, Fernandez sees it as an important early influence on Jobs’ sense of design and love of minimalism. Jobs was around so often and endeared himself to Fernandez’s mother so much that she thought of him like another son, Fernandez said.

While both Fernandez and Jobs loved technology — it was their most important common bond — the two of them were also a pair of deep thinkers at a young age, and they liked to explore ideas together. One of the things they did more than anything else was to walk.

“He and I also spent endless hours walking around the neighborhood, particularly in some of the nearby, undeveloped wild lands, talking about life, the universe, and everything,” said Fernandez.

For Jobs, it was a pattern that lasted his entire life and career. With Apple employees, Silicon Valley colleagues, journalists, and friends, the favorite meeting place of Steve Jobs was the open air of Cupertino or Palo Alto on a good, long walk.

Download this article as a PDF in magazine format (free registration required)

The first hire

It wasn’t long after he introduced Jobs and Wozniak that Fernandez noticed the two of them hanging out on their own. They collaborated on two things: electronics projects and practical jokes. Eventually, the two of them starting working on professional projects together when Jobs landed a gig with Noah Bushnell at Atari and enlisted help from Wozniak in creating the game “Breakout.”

Then, famously, Jobs and Wozniak started a little computer company called Apple when Jobs decided that the computer Woz had designed, later to be known as the Apple I, could be packaged and sold to other enthusiasts. Jobs was into the company more than Wozniak. Woz had an excellent gig working as an engineer at HP, and at the time he could happily see himself working there forever. But, as the computer revolution was preparing to take flight, HP didn’t include Woz in its team that was working on a personal computer. So, he scratched his itch to build a computer with the fewest possible parts by sketching ideas and experimenting with prototypes in his spare time.

As the Apple I evolved into the groundbreaking Apple II, it was time for Jobs and Wozniak to start a company. Woz was unsure whether Apple would rise above the scads of decloaking computer companies that wanted to pioneer a personal machine, so he wasn’t ready to leave his job at HP yet.

Jobs, on the other hand, was all in. But, he needed help. So Woz and Jobs approached Fernandez, who was working with Wozniak at HP at the time. As Fernandez remembered it, they told him they needed an electronic technician and he was the best one they knew, and would he come work for them at their little company.

Fernandez thought about it and said to himself, “These are a couple of my friends, and not corporate types with a lot of stability, and I’ll be working in a garage. But, I’m living from home, and I’m not married.”

So he took a chance.

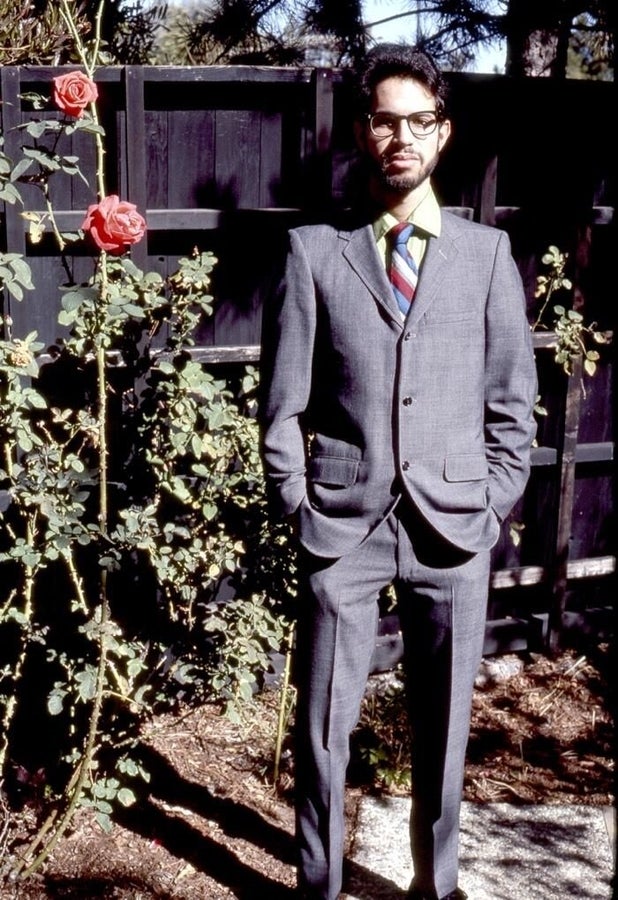

Apple was not even officially a company yet, and Fernandez had to delay working for Jobs and Woz until he gave his notice at HP. But, when he came on board in early 1977 it was just as Mike Markkula became an investor and Apple Computer, Inc. was officially formed. Fernandez became the first official full-time employee.

Wozniak said, “Bill was really in that early circle of founders at Apple. He was part of the family. He [later] got badge number four, but we really brought him in before Mike Markkula [who got badge number three].”

Kottke said, “There are three people who can claim to be Apple’s first employee: me, Bill, and Steve’s little sister, Patty. Patty was actually getting paid a dollar a board to plug chips into the Apple I board. That was in the early summer of ’76. And then in June of ’76 I showed up, and it was an easy choice for Steve to give that job to me. I never knew that he had been paying her a dollar a board. He was paying me three dollars an hour, and I could do way more than three boards an hour. So I was Steve Jobs’ first cost reduction. He could have offered me the same dollar a board he paid his sister. So at that point I could say I was the first employee. But then at the end of the summer I left to go back to Columbia to finish my degree. And then in January of ’77 Apple incorporated, and then there was money and Bill Fernandez was hired.”

While Apple was now a company, it was still barely formalized.

Fernandez put it in perspective. “Jobs and I used to take turns going over to each other’s garages, typically, and hanging out there and working on things,” he said. “I’d bicycle down there, and he’d bicycle over to my house. But now I found myself in my little yellow Datsun pickup driving over there and going to work in the garage, which was kind of funny. And as things happened, we built things, we built boards, we brought in processor technologies to look at.”

Now the two of them were carrying the daily weight of a nascent company on their shoulders. Since Fernandez was the technician, it was his job to help assemble and solder and build things and offer feedback and input. As the only employee, he also ran errands all over the place to do whatever the company needed.

“It was just me. And for a long time it was just Jobs and me because Woz was still working at HP,” said Fernandez. “Jobs and I were in the garage. Woz was in between HP and his apartment… It was incredible. I’d be sitting in the garage and Woz would come in and say, ‘You gotta see this program.’ … Things were always happening and always growing and always moving forward. There was always forward motion.”

The Apple I had been a respectable start, but the Apple II turned into a runaway success. Apple outgrew the garage and moved into its first office on Stevens Creek Boulevard in Cupertino. Woz quit his day job at HP and came to work at Apple full time.

“There was magic in the air. There was a palpable sense that magic was in the air,” said Fernandez. There was also this implication that we were going to change the world, or we were going to change society in a significant way… [There was] the sense that anything was possible, that we were fulfilling the growing demand and desire for people to own their own computers, that we were empowering ordinary people to do things unimaginable, that we were putting the latent, potential power of technology into the hands of the people.”

But, as Apple skyrocketed into an icon of the emerging computer revolution and Jobs and Wozniak became geek heroes, some of the early Apple employees got lost in the shuffle.

Fernandez was among the lost.

Once Rod Holt was hired to run engineering, he became Fernandez’s boss. Fernandez was a very capable technician who helped shape the early trajectory of Apple and the products that made it a success. But as the startup transformed into a corporation, Fernandez remained a technician and increasingly ended up doing unfulfilling kinds of work. “It was mind-numbingly boring,” he said.

He and Holt got along well, but when Fernandez approached Holt about opportunities to move forward, there weren’t many options. At that point in 1978, Apple was up to 100 employees and was catapulting toward an IPO. It was an IPO that years later would create more capital than any since Ford Motor Company and would set a new all-time high by creating over 300 millionaires.

But, in 1978 as Bill Fernandez was looking for opportunities to do more at Apple, the word was starting to get around about employees getting a stock option. There was no human resources department to handle the issue and explain it to employees, but it was becoming clear to some employees that not everyone was going to get a stock option.

“It was only a big deal to those of us who didn’t get one, which there weren’t many. There were very few of us,” said Kottke. “The policy of the company was only engineers. Apple was not unusual in that regard. That was common. Secretaries did not get stock options. Hourly employees, in general, were not eligible — only salaried engineers. [Bill] was the hourly technician in engineering, and I was an hourly technician in production.”

So, with little hope of doing more than assembling prototypes as a technician and no prospect of getting a stock option, Fernandez decided to leave Apple just 18 months after joined the garage as the first guy that Jobs and Woz wanted to hire. His friends were now busy and overwhelmed trying to run a company in their 20s, and quiet, humble Bill Fernandez got lost in the background.

“There was no growth path for me,” said Fernandez. “I was a pretty naive, geeky kind of guy… As the company grew and as we hired more and more high-level people, I became bored and dissatisfied with working at a technician level and never having the opportunity to grow into an engineer.”

Bill got a job offer from some people he’d worked with after high school. They had started their own company making computer components, and they gave Fernandez the opportunity to come work for them as a product engineer.

“So I left Apple to get some career growth,” said Fernandez.

He said he also left because “it meant I could actually invent things and create things.”

Unfortunately, it turned out that the company and its technology needed a lot of cleaning up, which meant that Fernandez ended up doing a lot of the same kind of technician work that he was fleeing at Apple. So, it didn’t work out. After a year, Fernandez walked away, unsure of where to go next in his career. Meanwhile, Apple II sales continued to explode, and Apple Computer, Inc. prepared to go public with one of the blockbuster IPOs of the 20th century, turning many of his Apple friends into millionaires.

Fernandez said, “We make choices in life and choices have consequences… And you go forth in life making a series of consequences.”

Download this article as a PDF in magazine format (free registration required)

The computer that love built

After leaving the component maker, Fernandez took his life in a completely different direction. He got out of technology. He searched for bigger meaning. He left the country.

“I have always had too many interests,” he said.

One of those interests was the martial arts. Fernandez was a brown belt in Aikido, a Japanese form of the martial arts that is primarily defensive and centered around the concepts of peace and unity. The curiosity about Japan and the Far East that he inherited from his mother, combined with his own studies in Aikido, compelled Fernandez to leave Silicon Valley for Japan in 1979.

“I got a cultural visa and then went over there and lived there for two years,” said Fernandez. “I got to go and live in a country where I had a lot of interests and kind of immerse myself in the culture.”

He settled in Sapporo on the northern island of Hokkaido, which is about the same latitude as southern Alaska. “It’s snow country for Japan,” said Fernandez.

Fernandez went to Japan to do a combination of three things. He worked as an English teacher and tutor for adults. He studied Aikido more deeply to earn his first degree black belt.

He served as a cultural ambassador for the Bahá’í Faith, a religion focused on building a global community through international fellowship.

“I taught English to support myself,” Fernandez said. “At that time, there was a huge interest in having native English speakers tutor people in English. So I had a small group at a bank and a small group at an engineering firm… So that was part of my day. It was preparing lessons and teaching classes. And then part of it was just immersing myself in the culture… Being an American there, people were interested in that. So people would come out of the woodwork and become my friends and sort of set up cultural experiences for me.”

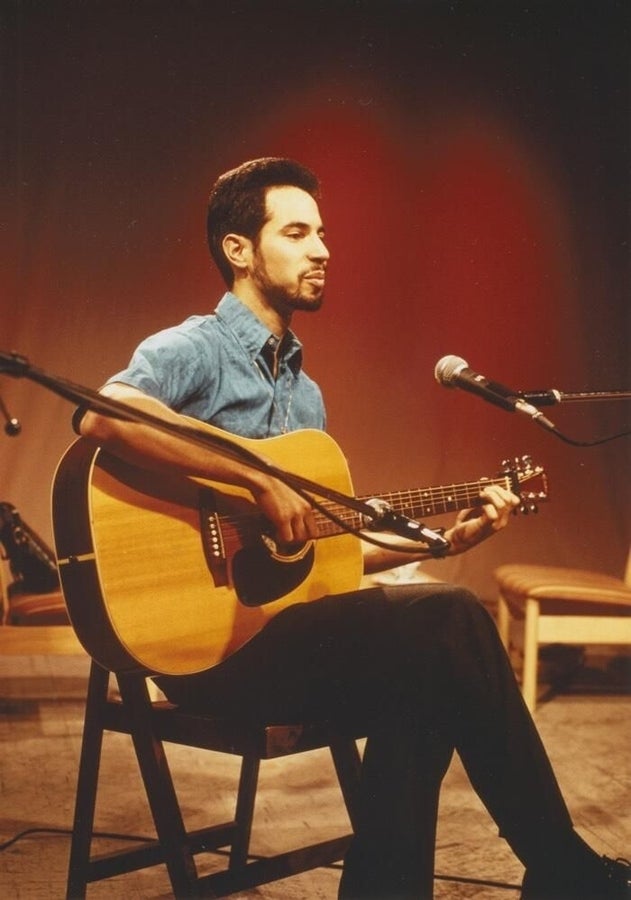

In Japan, Fernandez also got to engage his interests as a musician and humanitarian.

“In Sapporo, the Bahá’ís sponsored a charity concert for UNESCO where I was a performer … to sing and talk about California. So I called it the ‘Refreshing California’ concert. I sang songs and showed slides of California cities and farmland and talked about what it was like, because America looms large in the Japanese psyche, and California is one of the places that’s kind of famous and has kind of a character that attracts the Japanese imagination.”

But after two years in Sapporo, in the spring of 1981, it was time for Fernandez to return to California. When he landed in Silicon Valley in search of work, Fernandez gravitated back toward some familiar friends.

“When I came back, I got into technology because that is what I knew,” he said.

He did some freelance and consulting work for several months, and he also reached out to Steve Jobs. Fernandez said to him, “I need a job. Have you got anything interesting?”

Jobs certainly did.

At the beginning of the year Jobs had taken over the Macintosh project. He was fighting to remain relevant within the leadership team at Apple — which now had a bunch of experienced executives in its ranks — and so Jobs had set up a separate SWAT team of engineers and designers to build a different kind of computer than the Apple II. For this team, he was adding technologists that he knew and trusted. He only wanted the best.

In October 1981, Jobs hired Fernandez to come back to Apple as a “Member of Technical Staff,” the 15th member of the Macintosh team.

Because Fernandez had previously been an Apple employee and his name was already in the company’s database, he was re-issued the same employee number he had before he left in 1978: No. 4.

Apple was a much different company the second time around, with thousands of employees, high-powered executives, a corporate infrastructure, and a growing campus of buildings in Cupertino.

But Jobs separated the Macintosh team from Apple headquarters by putting the group into a two-story building several blocks away from campus. It was next to a Texaco station, and so the team members dubbed it “Texaco Towers.”

While the Apple II was still selling like crazy, Jobs predicted that it was destined to run out of steam within a couple years and that Apple needed something much more audacious to remain a leader in the computer business. IBM and a flood of other companies were coming into the market with new products that were creating brutal competition.

The Macintosh project was something the Apple executives allowed Jobs to dabble with — partially in hopes that it would develop into the company’s next great product, but partially just to keep him busy and out of the way.

Jobs fired up his band of rock star techies to create a new kind of computer that would change the world, unleash the latent creativity inside of people, and bring the power of the computer revolution to everyday people. While he was notoriously difficult to work with at times during this period, he could also be deeply inspiring.

“The Macintosh development was basically an environment filled with love — love for our loved ones and our family members, because these were the people we kept in mind as our target audience,” said Fernandez. “It was hugely creative, and we knew that we were breaking new ground and that we had to invent a new world, a new way of looking at things, a new way of interacting with things. It was a very creative, inventive environment where a whole lot of hard work was being done to do that and a whole lot of hard thinking about how do we accomplish our goals, and it was all motivated by wanting to do something insanely great that would serve our loved ones. There was all of that — love, creativity, hard work, inventiveness, vision, drive. So it was a wonderful environment.”

Fernandez moved into a role similar to what he had played in the early days in the Apple garage. He was a utility man, a jack-of-all-trades, the person who filled in the gaps.

“I played a lot of different roles,” said Fernandez.

One of those early roles was as the manager of the engineering lab. Another was engineering project manager for projects like the Macintosh External Disk Drive and the Macintosh External Video Port. At another time, he was the project manager for the AppleTalk PC card.

When the Mac team finally moved out of Texaco Towers and into the “Bandley 4” building on the Apple campus, Fernandez worked with the architects to plan the move and make the space a great working environment for the team. That included “laying out the hardware lab, and building a no-doors-needed ‘light lock’ leading into and out of the CAD room, putting trees along the division between the main hallway and the break area,” said Fernandez. And “putting planter boxes with trailing vines, etc. along the tops of cubicle walls to spread greenery through the office area in a space-efficient way.”

One of the skillsets that Fernandez was developing along the way was designing interfaces for humans — both virtual interfaces and physical interfaces. The Mac team turned out to be an amazing place to cut his teeth on these ideas because the team dove deeply into the concept of user interface and how to build a new one that average people could intuitively understand. They famously settled on the metaphor of a physical desk, and they imposed a tremendous amount of discipline on themselves to design a system that wouldn’t confuse users.

“On the Mac team, we were trying to bring the illusion of tangibility to the screen,” said Fernandez.

The Mac engineers went to a tremendous amount of effort to standardize the look and behavior of the different controls in the operating system. They thought deeply about checkboxes versus radio buttons, for example.

“All of those things we consciously thought about how do we make a pattern of visual elements that communicate their function and how do we make patterns that give you a consistent way to interact with your program, no matter what the program was,” said Fernandez.

“We really tried to get all the third-party developers to write programs so that they all kind of worked in the same way, so that users would have to learn essentially one language — one visual language, one user interface language, one interaction language, one behavior language — that they could then apply to all of the apps that they bought. That had a powerful force in the industry. And everyone kind of copied those patterns.”

When the first Macintosh computer arrived in January 1984, it included a secret buried deep inside of it on the molding of the case. The signatures of the members of the early Mac team — including Bill Fernandez — were emblazoned on the lining.

“The Mac team had a complicated set of motivations, but the most unique ingredient was a strong dose of artistic values,” explained Mac engineer Andy Hertzfeld in an article about the early Mac team. “First and foremost, Steve Jobs thought of himself as an artist, and he encouraged the design team to think of ourselves that way, too… Since the Macintosh team were artists, it was only appropriate that we sign our work. Steve came up with the awesome idea of having each team member’s signature engraved on the hard tool that molded the plastic case, so our signatures would appear inside the case of every Mac that rolled off the production line.”

The signature panel was created on February 10, 1982, almost two years before the product launched, and had 47 signatures, including Fernandez, Hertzfeld, Kottke, Jobs, and early Mac pioneers like Jef Raskin and Bill Atkinson.

Another one of the signatures on the panel was three simple letters: “Woz.” Wozniak had been part of the early Mac team, mostly helping conceptualize what the Macintosh should be and helping with the early processor design.

Around the time of the Apple IPO in late 1980, Woz decided to give away stock options to the earliest Apple employees who had never gotten options — including Randy Wigginton, Chris Espinosa, Kottke, and Fernandez. He gave them each a stock grant out of his own chunk of shares. It was a generous move, especially towards Wozniak’s old neighbor and friend with whom he’d built his first computer and helped become Apple’s first employee.

“Bill is one of my favorite people in the world,” said Wozniak. “What I really respected the most about Bill was his mind. He was so clear-headed.”

Download this article as a PDF in magazine format (free registration required)

Leaving Apple again

After the launch of the Mac, Fernandez remained at Apple for nine more years. In 1986, he moved from tinkering with hardware into building software interfaces, where he discovered his niche and eventually developed a reputation as a UI wizard.

“I found that I had an affinity for user interface work and gradually migrated from electronic engineering work to user interface design,” said Fernandez.

In the Apple and Silicon Valley tradition of thumbing its nose at corporate America and taking on tongue-in-cheek job titles, Fernandez adopted “Master of Illusions” on his Apple business card.

He went on to play a key role in the development of QuickTime and HyperCard, which had a big influence on the development of HTML and the world wide web. Fernandez was also instrumental in the evolution of the Macintosh Finder system software. One of his last big projects at Apple was designing some of the MacOS 7 folders, including the three-button concept for opening, closing, and maximizing that still remains to this day.

In 1993, “Apple had started laying off long-time veterans, presumably to save money by getting a lot of highly-paid people off the payroll,” said Fernandez. “I was in the second round of these layoffs during that period.”

Fernandez called the experience “liberating.” He immediately got several job offers for his services as a UI expert. He worked for a database company that was acquired; he worked for a document management company that went on to an IPO; and then in 1998, he started his own company, Bill Fernandez Design, a UI consultancy. He did that for 15 years, working on many different projects for many different companies that he can’t mention by name. He did that until 2013, when it was finally time for him to launch his own tech startup.

The future of UI

With a front row seat to the birth of the personal computer and the rise of the internet — and a key role in several of the technologies that helped shape those revolutions — Bill Fernandez has accumulated enough wisdom to fill a library. It gives him a ready perspective on the hottest issues in technology today, and the stuff that’s going to shape the future of computers, design, and UI. Especially UI.

“We are in a time of transition,” said Fernandez. “And like [how] the water becomes brackish where river water meets the ocean, the state of UI design is messy. There’s some great stuff out there, much more than there used to be, but there’s still a lot of trash, and there’s a lot of well-meaning but misguided efforts. One example of this is in the migration from three-dimensional, photo-realistic UI elements (window frames, pushbuttons, sliders, etc.) to ‘flat’ UI design. Years ago a friend asked what I thought web pages of the future would be like and I said ‘like magazines.’ I thought we’d see flatter designs, expert typography, beautiful, magazine-advertisement-like page layouts, etc. That prediction is coming true…

“But in moving towards flat design we are losing much of the wisdom that was embedded in the old 3D style of UI. For example: A user must be able to glance at a screen and know what is an interactive element (e.g., a button or link) and what is not (e.g., a label or motto); A user must be able to tell at a glance what an interactive element does (does it initiate a process, link to another page, download a document, etc.?); The UI should be explorable, discoverable, and self-explanatory. But many apps and websites, in the interest of a clean, spartan visual appearance, leave important UI controls hidden until the mouse hovers over just the right area or the app is in just the right state. This leaves the user in the dark, often frustrated and disempowered.”

Fernandez sees the current state of flat design as “a very mixed thing” and worries “we have lost a lot of the wisdom of the past, as we’re moving into a cleaner future.”

The startup

As passionate as Fernandez is about the ways people will use computers in the future, today his time is being spent designing a very specific kind of UI.

Almost 40 years after helping Jobs and Wozniak start Apple, Fernandez is launching his own tech startup, Omnibotics. The company is still in stealth mode at the time this article is being published, but Fernandez gave a few hints about its trajectory.

“Now that my kids are grown and I can ignore them without harm, I have closed my consultancy to follow my dream of starting a company that will transform how we interact with our homes. This is the future I’m most looking forward to. And we’re looking for rock star engineers, marketers, and investors who want to join the team,” he said.

He said Omnibotics will “build smart home electronics and I’m hoping that we can finally make it possible to make your house more responsive to you, to give your house a user interface other than mechanical switches and knobs.”

Wozniak said, “Because of his keen mind and his understanding of people, Bill is able to look at technology from the perspective of the viewer and design something that is usable.”

Badge No. 4

For now, history will remember Fernandez as “Badge No. 4” at Apple. Kottke, however, never remembers Fernandez flaunting, or even mentioning, his badge number — even though low badge numbers were very prestigious at Apple.

No photos exist of Fernandez with the famous badge, and he gave it to human resources when he left the campus for the last time as an employee in 1993.

“I was a good boy and when I left, I gave them my badge back,” said Fernandez. “Some people have ended up with their badges still in their possession. I don’t know how they did that. And I wish now I’d kept mine. [But] when you leave a company you’re supposed to turn in your badge.”

Perhaps no Apple employee has had a greater odyssey with the company than Bill Fernandez, with timeless contributions and disquieting exits. He never made millions from stock options. He never became famous as an early Apple pioneer. But he has a legacy of work that influenced some of the most important forces of change in our time, and he walked away with a wisdom that he continues to use to play his part in technology’s contribution to humanity.